Viewing: 12 - View all posts

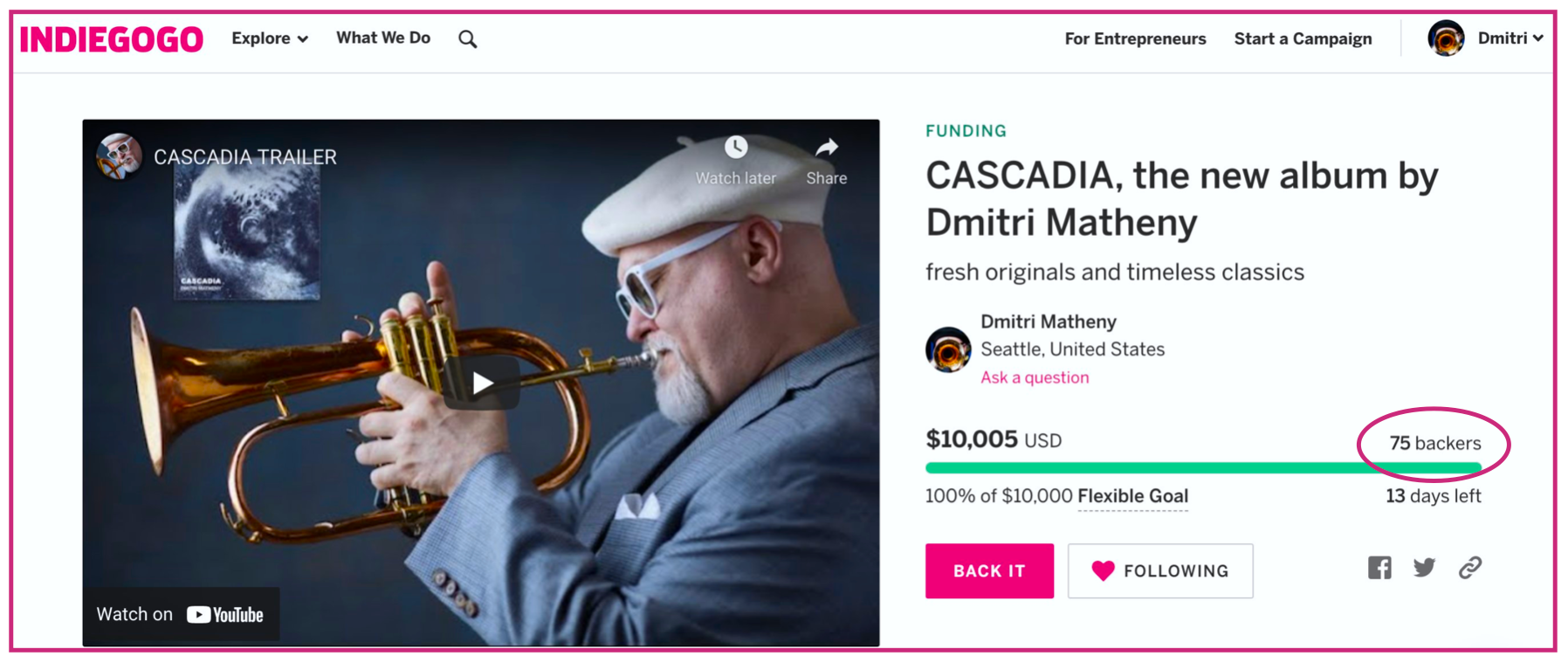

2021 BY THE NUMBERS

Well my friends, it may take several years before we can return to pre-pandemic levels of activity. But little-by-little we’re getting back to business, ever grateful for the clients, customers, friends and fans who sustain us. This year we:

staged 81 concerts and events

welcomed 75 generous album backers

published 50 memoir blog posts

published 50 memoir blog posts

gave 23 private lessons

conducted 19 workshops

collected 12 vintage treasures

collected 12 vintage treasures

recorded 10 songs

headlined 9 festivals

bottled 8 jars of homemade hot sauce

completed 7 new compositions

played 5 live stream shows

played 5 live stream shows

traversed 4 western states

received 3 doses of DollyVax

hosted 2 brilliant visiting artists

rescued 1 precious puppy

and consumed 2197 hours of television (sigh).

Here’s to a happier, healthier, and more productive 2022.

Onward and upward!

~Dmitri

SNAPSHOTS | PART 4 — CHUBASCO

“Your vibe attracts your tribe.”

—Anthony Bourdain

“We go back like car seats.”

—Harry Bosch

It can’t be an easy thing to raise a son.

It’s a balancing act. To help him find his way in life while also allowing him the freedom to fail. To provide advantages and opportunities without coddling or spoiling him. To encourage excellence without setting unrealistic standards. To teach him both self-confidence and humility. To know when to protect him, when to counsel him, and when to let him face adversity alone. To balance his needs with your own.

My father did his best. In 1978 when he decided to relocate us to Arizona, he had his reasons. He was heartbroken, depressed, and needed a change. The move proved troublesome for me, but I don’t begrudge Dad needing to prioritize his own mental and emotional health. It was never his intention to sabotage my education or put me in harm’s way. Kids are resilient. He knew I would adapt.

It didn’t take Daddy Bill long, however, to realize that Marana was no place for either of us. He loved to teach but was spending most of his time enforcing classroom rules and trying to maintain order. I loved to learn but none of my classes were interesting, and I was always on guard, looking over my shoulder for the next attack.

Dad resolved to seek employment elsewhere as soon as his contract was up, and promised he would find a better school for me in Tucson the following year. In the meantime it was my job to survive seventh grade at Marana Junior High.

Fortunately, life got easier for me at Marana. There was still plenty of student-on-student violence but somehow I was no longer a target. Is it because I carried myself differently after I’d learned a few moves? Possibly, but the more likely explanation is that I was spared because I finally made the right friends.

I met Jack in Reading class (no joke, the class was called “reading”), and we hit it off immediately. Jack was different from the other kids. Like me, he was a displaced southerner (his family came from Virginia) with an artistic bent and diverse interests. He was smart, articulate, creative, and funny as hell. He was also an excellent writer. In fact, the only time I ever got in trouble at Marana, it wasn’t for fighting, but for laughing at one of Jack’s hilarious short stories.

Jack was smart, articulate, creative, and funny as hell.

Jack was smart, articulate, creative, and funny as hell.

“Settle down, Dmitri,” said Mrs. Woods.

“Yes, ma’am,” I replied.

“Don’t back-talk me! You go to the principal’s office right now!” she demanded.

I told Principal Dewey that Mrs. Woods had misinterpreted my sincere polite response as sarcasm. “It’s how I was raised,” I explained. “At my old school in Georgia, you’d get in trouble if you didn’t say yes ma’am.”

“Well, you’re here now. Lose that habit,” he said. “And I still have to give you detention for disrupting class.”

“Yes, sir,” I replied, true to my roots.

A few days later my new friend Jack introduced me to his pal Bennie, a charismatic football player with a winning smile and a terrific sense of humor. Bennie had cracked the code on how to flirt, too, and all the girls giggled whenever he was around. Ben’s upbeat attitude was infectious. I liked him right away and the three of us soon became fast friends. It didn’t surprise me at all when I later found out my new companions also happened to be Dad’s favorite English Lit students.

Bennie’s upbeat attitude was infectious.

Bennie’s upbeat attitude was infectious.

No fights found me after I started hanging out with Bennie and Jack. In a school where sports participation is one of the only real forms of social currency, the two of them were well-liked student athletes. They seemed to get along with everybody, even the so-called bad kids. I must have benefitted by association. Plus, Jack was taller than almost everyone else in our class. Nobody messed with him.

We were the original three amigos. We hung out everyday at school and sometimes on the weekends. I liked to draw comic books for fun back then and remember creating Jack Fox and Blazin’ Ben as their superhero alter egos.

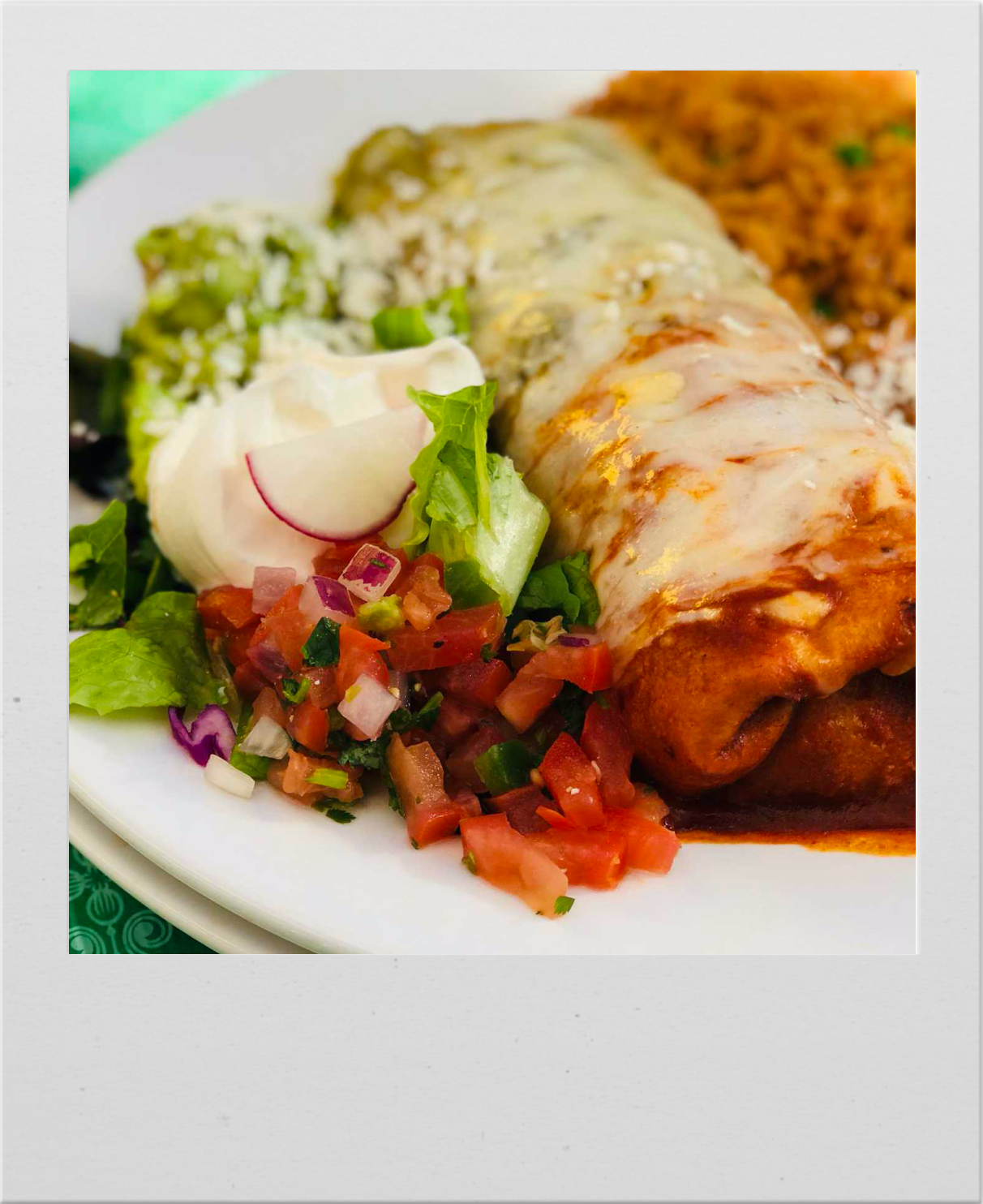

For all its faults, Marana did one thing 100% right: almuerzo, or as we called it, lonche. Twenty-five cents would get you a man-sized portion of delicious Sonoran food, served up fresh daily in the school cafeteria. The ladies in the kitchen took great pride in their work and prepared a different main course for us each day: carnitas, tamales, machaca, fajitas, chile rellenos, enchiladas verdes, and more, always with a generous helping of frijoles refritos con arroz. Damn, I loved those Marana lunches.

Damn, I loved those Marana lunches.

Damn, I loved those Marana lunches.

The other thing that made lunchtime so great was the game we always played. Bennie, Jack and I, and occasionally our friend Kevin, would take turns trying to make each other laugh with ridiculous jokes, silly voices and wordplay. Sometimes we would mimic absurd Steve Martin comedy routines or reenact entire skits by the Not Ready For Prime Time Players. Invariably we’d all end up doubled over in fits of laughter. The game never ended until the bell rang or Bennie spit milk out of his nose. Big fun.

I loved those guys then and I love them still.

I had no way of knowing, at the time, that Bennie would grow up to become one of the west coast's most popular radio personalities, or that he and his wife would generously let me stay with them while I found my first apartment in San Francisco. I couldn’t have known that Ben would one day introduce me to the O’Jays (with whom I would have the honor of working some years later), or how supportive he would be over the course of my future music career. I didn’t know that Ben and I would remain friends for life.

And I certainly had no way of knowing, at the time, that Jack and I were destined to attend the same high school in Tucson, become college roommates in Boston, and remain close as adults as we both pursued careers in the performing arts. I couldn’t have known how much time we would spend playing in bands with each other, or discovering music together over many late nights at the turntable, poring over liner notes as we listened to his excellent collection of classic jazz on vinyl. I didn’t know we would one day stand up as “best man” at each other’s weddings, or that we would continue to confide in one another, sharing our troubles and triumphs well into late middle age. I didn’t know that Jack would be my best friend forever.

All I knew was that I had finally found my tribe. I'm not sure whether I ever told them how our alliance had saved me. Jack and Ben made an otherwise miserable year not only bearable, but memorable in the best possible way.

On December 25, my father and I celebrated the holiday on our balcony, grilling steaks and listening to our favorite seasonal album, Ella Wishes You A Swinging Christmas. After dinner we watched as heavy, dark clouds rolled over the valley, showering the desert with a wondrous cleansing rain.

We watched as heavy, dark clouds rolled over the valley,

We watched as heavy, dark clouds rolled over the valley,

showering the desert with a wondrous cleansing rain.

The winter cloudburst felt auspicious, like a baptism or benediction.

“Merry Christmas, Daddy Bill,” I said.

“Happy Birthday, Bub,” he said. “You’re a teenager now.”

“Yes, sir,” I replied, true to my roots.

SNAPSHOTS | PART 3 — TANGLE

“The beginning of things is necessarily vague,

tangled, chaotic, and exceedingly disturbing.

How few of us ever emerge from such beginning!”

—Kate Chopin

By summer’s end I’ve discovered much to love about living in Arizona.

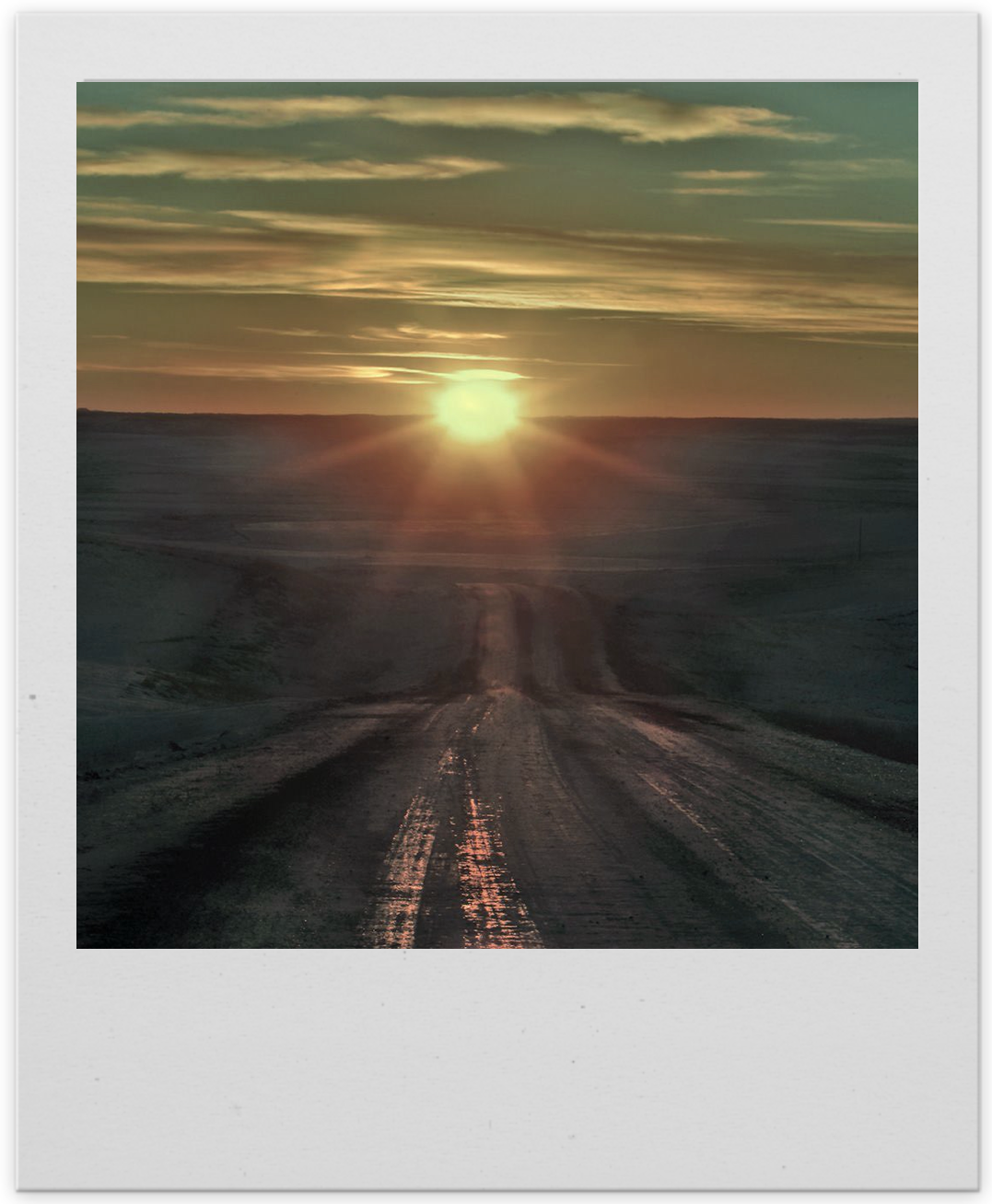

The regional art, music and food are outstanding. The laidback lifestyle suits my temperament. The arid landscape is as vast and peaceful as the ocean. I like the way hawks wheel and keen overhead as the majestic saguaro watch silently like sentries. And most of all, I love the glorious sunsets.

Some part of me knows my future lies elsewhere. If books and movies have taught me anything, it’s that one day the call to adventure will require me to leave this desert. In the meantime, this seems like a good place to begin the next chapter of life’s journey.

If books and movies have taught me anything, it’s that one day

If books and movies have taught me anything, it’s that one day

the call to adventure will require me to leave this desert.

Today is the first day of school. Daddy Bill and I are up early for our commute to the town of Marana, just northwest of Tucson. The drive is pleasant. The sky is overcast so it’s a little cooler than usual. The university jazz station is spinning some classic Miles, always a good omen, and our little Toyota still has its new car smell.

My spirits are high. I’m excited to begin seventh grade, although I’m not entirely sure what to expect. None of the kids in our 22nd & Craycroft neighborhood go to school out there. I only know what Dad has told me, that it’s a public school in a rural area which takes its name from the Spanish word “maraña,” meaning tangle. And last week I overheard Dad on the phone saying something about “teaching basic English to the children of migrant farmworkers.”

This morning as we travel the long frontage road past dusty acres of alfalfa and cotton, I begin to understand. “Things are going to be a little different here than they were at Brookstone, son,” Daddy Bill says. “Just be patient and keep an open mind.” It sounds rehearsed, like a prepared speech. I have the feeling he’s talking to himself as much as to me.

As we travel the long frontage road past dusty acres

As we travel the long frontage road past dusty acres

of alfalfa and cotton, I begin to understand.

Dad was an important man at Brookstone School, and because of his position, I pretty much had my run of the place. I literally grew up there, kindergarten through sixth grade. I knew everybody, even the high school kids, and always felt safe and supported. Saying goodbye to Brookstone was the most difficult part of leaving Georgia.

My favorite class at Brookstone was a sixth grade social studies elective called MACOS: Man A Course of Study, in which we compared innate and learned behavior in humans with that of other primates, then presented our findings to a panel of university graduate students. Our instructor James Stockdale, son of the homonymous war hero, was my favorite teacher. He taught us to be curious, question all assumptions, and believe in ourselves.

Brookstone School cast a long shadow over my life. I thrived there, but since it was the only school I’d ever known, I took its brilliant faculty and innovative curriculum for granted. I didn’t realize how fortunate I was to attend such an elite private school. I wasn’t aware that we were poor, that my classmates were rich, or that my tuition had been waived as part of Dad’s teaching salary. And I certainly couldn’t have known, at the time, the degree to which being part of that nurturing scholastic community had shaped my nascent love of learning, positive self-image and sense of entitlement.

Brookstone School cast a long shadow over my life.

Brookstone School cast a long shadow over my life.

I only knew that I enjoyed school. Or so I thought.

For Dad to describe Marana as “a little different” would prove to be the understatement of the century. Far from the stately red brick lecture halls and leafy woodlands of Brookstone, the Marana campus is little more than a few cement buildings and mobile classroom trailers surrounded by dirt, asphalt and gravel.

Based on the school’s exterior, I’m prepared to be underwhelmed by whatever awaits inside. But nothing could prepare me for the physical and emotional trauma I’m about to endure at Marana Junior High School.

I show up guileless and confident, ready to hit the books and eager to make friends. But for the first time in my young life, I simply don’t fit in. Back home I was a popular kid who excelled in music, art and academics, but my study skills and work ethic are meaningless here. The only things that seem to matter at Marana are football and fighting.

There are fist fights every single day at Marana. Clashes erupt spontaneously, for no reason and without warning.

For the first week I’m able to keep my distance. I watch with detached curiosity as the other students beat each other’s brains in. I wonder what Mr. Stockdale would think of all this violence. Is it innate or learned? And why don’t any of the teachers try to put a stop to it?

There are fist fights every single day at Marana.

There are fist fights every single day at Marana.

Later I would learn that Dad had actually tried to separate two kids who were fighting, only to receive a dressing down from his boss. “Never, ever lay your hand on a student for any reason,” Principal Dewey cautioned, “or we could be sued.” Dad was flummoxed. “Even if they’re about to kill one another?”

I’m mystified by all the aggression, but naively not afraid for my own safety. I’m new here. I’ve made no enemies. Plus my dad is on the faculty. No one would dare. But the main reason I feel secure is because I’m a good boy. I don’t get into fights. I get along with everybody … right?

Wrong. A skinny little southern boy with no friends who doesn’t play football? A teacher's kid, who struts around with his nose in the air, talking funny, using big words, acting all cocky and superior? At Marana Junior High this is a kid who needs a beatdown.

At Marana Junior High this is a kid who needs a beatdown.

At Marana Junior High this is a kid who needs a beatdown.

I’m walking to my locker after gym when out of nowhere someone shoves me against the wall. “What the hell?” I react, more startled than afraid. But before I can even get a look at my assailant he's knocked me to the ground.

The jackals encircle us, laughing and cheering. By the time I realize we're fighting it’s too late. The kid's knees are already pressed against my upper arms, pinning me to the concrete floor. I can't move. I'm practically immobile as he punches me repeatedly in the face.

Nobody stops the fight. Neither of us are punished. I’m literally saved by the bell as everyone goes to class, leaving me alone and vanquished. I never even learn the kid’s name or what motivated him to attack me in the first place.

After my nose stops bleeding I wash up and change my shirt. No cuts, just a few bruises. My head hurts and my ears are ringing, but I don’t look so bad.

On the drive home Dad doesn’t even notice that I’m hurt. This is a tremendous relief. I don’t want to get in trouble for fighting, and besides, I’m ashamed. My father was a champion boxer. If he finds out I can't defend myself I’ll be humiliated.

But I have bigger problems. Word gets around: the new kid doesn't know how to fight. It’s open season on Georgia Boy. I now have a target on my back.

Every few days somebody jumps me. It’s not like I’m being bullied, not like on TV. It’s never the same person and there’s rarely any preamble. Nobody threatens me or tries to take my lunch money. They just start shit. I never know when the next sucker punch is coming, or from which direction. And it’s this, the sheer senseless randomness of it, that terrifies me so and makes Marana my personal living hell. Never safe. Nowhere to hide.

I hate this school. I’m learning nothing here except how vulnerable I am. Some of these big, mean-looking boys with facial hair are obviously older kids who’ve been held back. One of them is so strong that he comes up behind me, picks me up, and throws me against the lockers.

But it isn’t only the big kids who pick fights. One day after school I’m walking to Dad’s janky classroom/trailer to practice my trumpet. I notice a group of athletes in my peripheral vision, but they’re all walking in the opposite direction so I pay them no mind. Suddenly a short freckle-faced kid with red hair breaks from the pack and runs straight at me. I flinch but stand my ground. I’m bigger than this one. He doesn’t scare me.

“I’m gonna kick your ass,” he says.

“I don’t even know you,” I say. “What’s your problem?”

“I think you’re a wet bag and a pussy” he snarls.

So I’m standing there looking at this little ginger lunatic, wondering what in the hell a wet bag could be, when he knocks the horn case out of my hand and tackles me. By now I know the drill. There’s no reasoning with these idiots. I land a few solid punches, but the impact does more damage to my fists than his face. The kid is small but he’s fast and knows how to grapple. He gets the better of me again and again. I can’t believe it: I’m losing this fight, too.

That evening the drive home is tense. Daddy Bill is silent and agitated. I look over from the passenger seat and notice he’s gripping the steering wheel so tightly that his knuckles are white. He's pissed. Did he see the fight? Am I in trouble?

Suddenly Dad pulls over, gets out of the car, and says “come here, dammit.” And right there, in the twilight, on the shoulder of the highway, my Golden Gloves-gone-pacifist father gives me the first of several lessons in self-defense. He shows me the boxer’s stance, some footwork, how to block and parry, how to throw a jab.

Right there, in the twilight on the shoulder of the highway,

Right there, in the twilight on the shoulder of the highway,

my Golden Gloves-gone-pacifist father gives me

the first of several lessons in self-defense.

“Don’t hit ’em in the head,” Dad says. “The head is hard. Hit ’em in the kidneys!”

The old man is full of surprises. I should have gone to him from the beginning.

Maybe I will survive this place after all.

Now all I need is a few friends.

Next:

SNAPSHOTS | PART 4 — CHUBASCO

SNAPSHOTS | PART 2 — FIRST CONTACT

“What makes the desert so beautiful

is that somewhere it hides a well.”

—Antoine de Saint-Exupery

Four days later we arrive, hot and tired, in the Old Pueblo.

Daddy Bill pilots our dusty U-Haul into an open parking space and squints upward through the windshield.

“I think that’s it, right up there,” he says, pointing to the third story. “Let’s check it out.” We’re both curious about this new apartment. Dad arranged the rental sight-unseen through an agency in Georgia. He mailed a check; they mailed the keys. Now we’re here.

I open the passenger side door and am nearly knocked over by the oven blast. “At least its a dry heat,” Daddy Bill says with a wink. “We’re definitely gonna need this,” he says, removing our portable ice chest from the front seat.

It’s late afternoon. The air is stifling. Cicadas buzz in the palo verde trees. We climb the exterior stairs, our footsteps echoing in the hollow cement stairwell.

The building itself is unremarkable, a typical example of the stark desert brutalist style of southwest architecture. Poured concrete blocks are stacked atop one another, textured with adobe and stained in shades of beige. There are rows of identical square windows, but nothing decorative, no arches, gables, or distinguishing features of any kind. This drab utilitarian structure could be anything: a factory, a hospital, a prison, you name it.

When we enter our apartment, however, I know we are home. On the opposite wall, sliding glass doors open to a balcony with a spectacular westward view. Brilliant hues of orange and violet paint the sky.

“Damn,” says Daddy Bill admiringly.

“What do you say we wait until dark to unload the truck?”

He reaches into the ice chest and hands me a cold one.

Watching the sunset from our balcony became a regular thing for us that summer, just as walking in the rain had been our routine down south.

Most mornings Daddy Bill would get up at the crack of dawn to go birding. “Gotta beat the heat,” he explained. Dad was smart that way, adapting to the climate, timing his excursions in synch with nature.

I, on the other hand, would blissfully sleep until noon, alone in the cool, dark apartment, lights off, blinds closed, swamp cooler cranked to the max. By the time Dad returned I would be on my second bowl of Raisin Bran and just about ready to start my day.

Like a fool I spent my afternoons outdoors under the relentless Sonoran sun, riding my bike, exploring. Whenever the heat became too much to bear, I would stop at the corner convenience store for a cold drink and a rejuvenating jolt of refrigeration. It was during one of these air conditioned interludes, standing in line at the Circle K, that I made first contact.

“You want a saleedo?” asked the girl.

She was blonde, tan, slender, freckle-faced, a little taller than I, and pretty, in a tomboyish Tatum O’Neal Bad News Bears sort of way. “I’m Cheryl,” she announced boldly, handing me a small, shriveled nugget of mysterious origin.

“Is it food?” I asked, dumbfounded. I studied the curious morsel she had placed in my hand. It was brown, misshapen, about the size of a buckeye, and dry as a bone. It looked like a piece of petrified animal scat.

“Just suck on it,” she giggled, popping one into her own mouth to demonstrate. I smiled. She smiled back.

Saladitos, for the uninitiated, are a Mexican snack of dried salted plums coated in chili and lime. Today you might find a sample in the international section of your favorite specialty food market. But back then, in the Summer of ’78, saladitos were a staple at every mini mart in Tucson, usually stored in a large glass jar right next to the cash register.

Cheryl consumed them like candy. “The best way to eat a saleedo is with a lemon or orange,” she stated matter-of-factly. “You cut the fruit in half, stick the saleedo in the middle, and suck out the juice. Soooo yummy.”

After that, the two of us were inseparable, riding our bikes every day on the street, along the sidewalk, and down the dry river beds, called “washes” by the locals. Cheryl was unlike any of the girls I knew back home. She was a wild child, free-spirited and fearless, always taking the lead, often getting into mischief, never waiting for permission to have fun. I was smitten.

One sweltering afternoon, Cheryl suggested that we go for a swim. “Do you know anyone with a pool?” I asked. “I know a place,” she answered cryptically.

To say we “snuck” into the Doubletree Hotel would not be accurate. Apparently a cute girl in a bikini can pretty much go wherever she pleases. Cheryl and I simply walked right in the front door and straight through the lobby, no questions asked. I was wearing running shorts, not swim trunks, but nobody cared. We parked ourselves poolside like hotel guests, ostensibly the entitled children of errant parents.

We had a blast splashing around in the Doubletree pool, teasing and taunting one another. I poked fun at Cheryl for being a juvenile delinquent, and she playfully mimicked my southern drawl, calling me “Jimmy Carter” and “Georgia Boy.” Eventually I remembered my dad and our sunset ritual, saying I should get home for dinner.

“Why don’t you come to my place?” Cheryl asked casually. “Just you, not your dad.”

The invitation took me by surprise. In all the time we’d spent together, Cheryl had never mentioned her home, and was weirdly evasive whenever I asked about her family. To me she was Feral Cheryl, untamed desert denizen. For all I knew she could have been a runaway.

We got on our bikes and I followed Cheryl home to a charming hacienda-style bungalow surrounded by colorful desert flowers, cacti in terracotta pots, and a welcoming ristra of chiles hanging over the front porch.

We walked around back and left our bikes by a large mesquite tree before entering the cottage through a side door. “Hellooo,” Cheryl called, kicking off her flip flops. There was no answer, but I wasn’t surprised. Something in the girl’s breezy, uninhibited manner told me what she already knew: we were alone.

“You hungry?” she asked. “I could eat,” I replied, trying to sound grown up. “I’m not ready for dinner just yet, but let me fix you something,” she said.

I then watched in amazement as my friend, still in her swimsuit, expertly prepared a cheeseburger just for me. I marveled at her casual, effortless skill as she sliced the ripe tomato, lightly toasted the bun, and browned the juicy burger in a cast iron skillet, all the while chattering away, hand on her hip, no big deal.

They say the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. I get that. Over the years I’ve shared many a special meal prepared by, or for, a beloved companion. But this was a first. I was just a twelve-year-old kid. No girl had ever cooked for me. The burger was delicious. If Jay could see me now, I thought.

Cheryl then pulled a styrofoam container labeled “Eegee’s” from the freezer, then led me by the hand to the living room sofa. “This is my favorite thing on a hot day,” she said, feeding me a spoonful of the frozen tropical treat. “Mm, hmm,” I responded approvingly.

“It’s even better with rum!” she giggles, producing a bottle from nowhere like a sleight-of-hand magician. “Now all we need is a little music.” I see a radio on the side table and turn it on. The wail of a saxophone fills the room with sound: “Baker Street” by Gerry Rafferty. I feel like I'm in a movie.

Cheryl rests her head against my chest.

She looks up. “Hey, how old are you, anyway?”

“Fourteen,” I lie.

“So ... you ever gonna kiss me?” she asks.

SNAPSHOTS | PART 1 — LEAVING

Childhood memories are like polaroid photos in an old dusty box.

They don’t provide a cohesive autobiographical narrative, only brief flashes of insight into the murky past. You sort through the random images, shuffling them like playing cards, until one of them finally whispers to you, and a shard of memory is revealed, darkly, like a half-forgotten scent or song fragment.

It is from these small, disparate clues that you must fashion your origin story. But each time you take the box down from the shelf, there seem to be fewer snapshots inside.

It’s the summer of 1978 in Columbus, Georgia. A U-Haul is parked in front of our little apartment at Warm Springs Court. Daddy Bill and I are loading our last few boxes into the back of the truck.

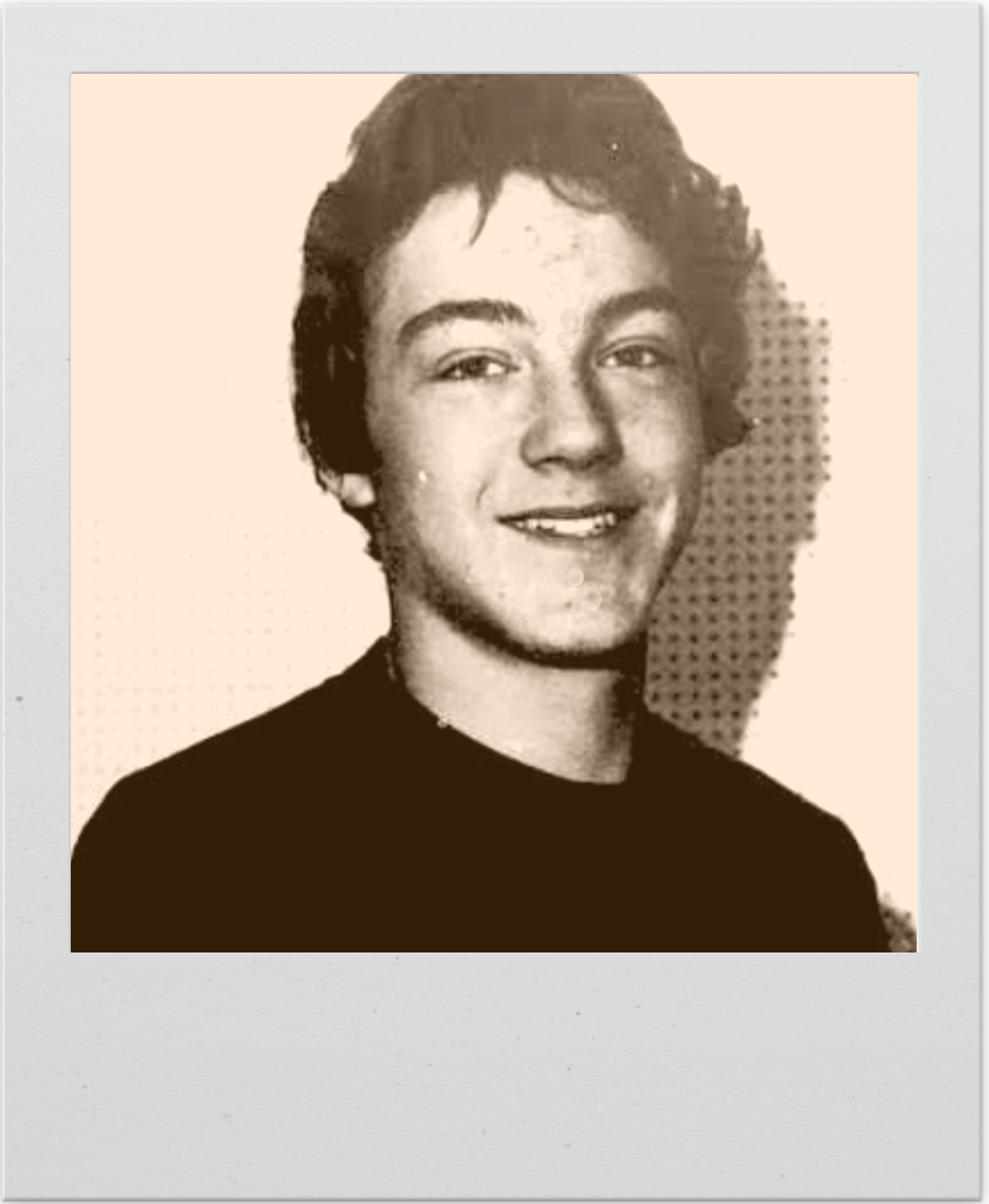

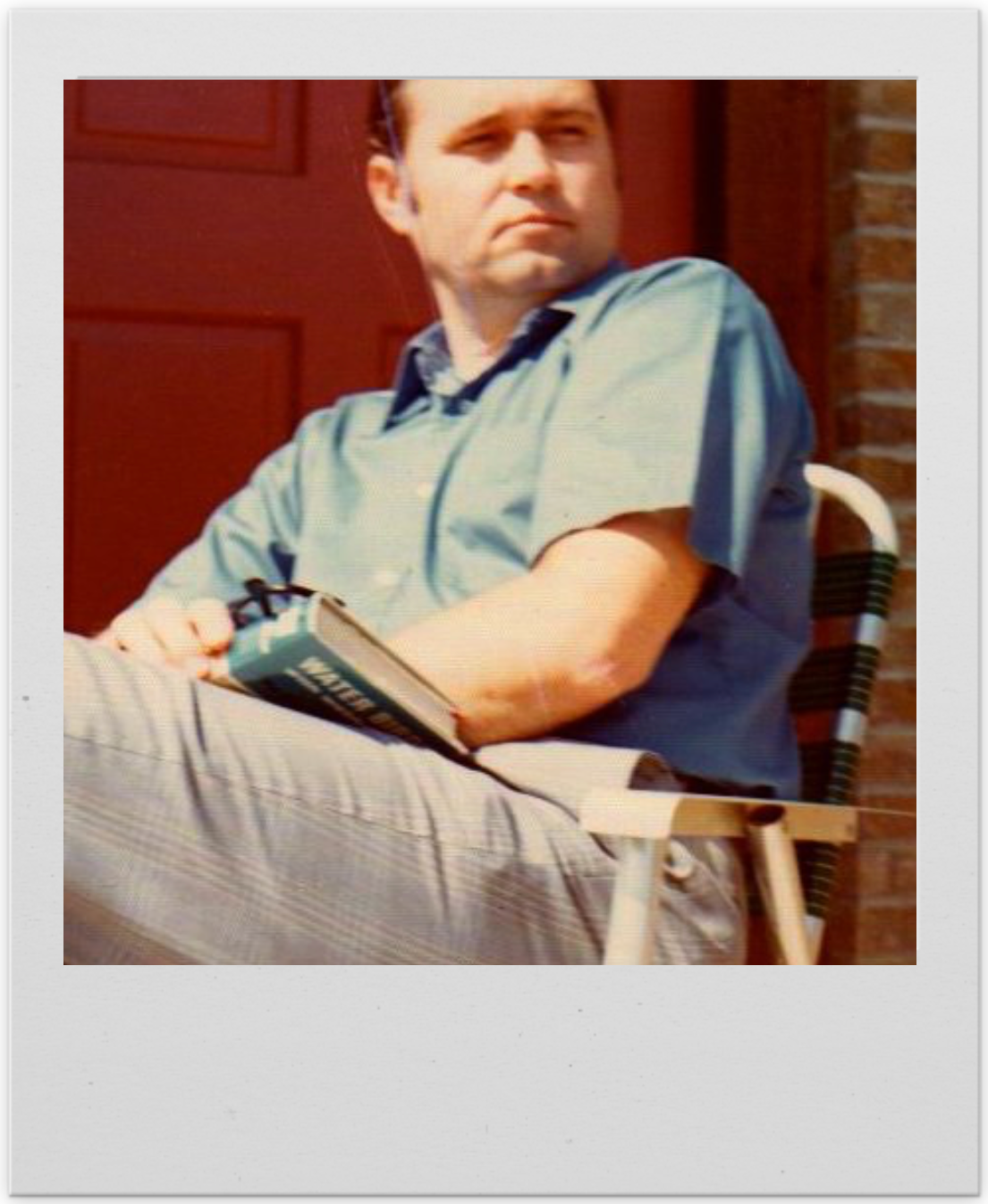

Daddy Bill Matheny | Summer 1978

Daddy Bill Matheny | Summer 1978

Warm Springs Court, Columbus GA

“You about ready to hit the road, Bub Man?” Daddy Bill asks. He’s been calling me “Bub Man” lately instead of Little Bub, and it feels right. I’m 12-and-a-half now, not a little kid anymore, and we’re about to begin a whole new life, far away from this place.

The past year was an emotional roller coaster. Up and down, love and loss. Dad finished his seventh year at Brookstone School on a high note, winning a prestigious teacher’s award from the city and having the yearbook dedicated in his honor. Then he abruptly resigned. Devastated by divorce, he slept for days at a time, rarely coming out of his room. “The doctor has me on tranquilizers,” he explained. When finally he emerged from the darkness of depression, other women came around, comforting him, playing mother to me, and we were happy for a time. But eventually they left, too.

When Dad’s last great love, Judy Mehaffey, moved to Nashville to pursue a songwriting career, her teenage son Jay came to live with us. Welcoming Jay into our home made sense. Our families were already intertwined. Jay’s mom and my dad, who still loved one another, were now prolific penpals. Jay’s older sister Kim, away at college, had been my babysitter and Dad’s star student at Brookstone. Kim and Jay’s father Lem (divorced from Judy, estranged from Jay) was the landlord of our little apartment complex.

Confused? Welcome to my world. The important thing is this: for one glorious summer I had a brother.

I was an only child who never especially wanted siblings. I cherished my solitude and was never bored. Daddy Bill and I were pals, and if I needed more companions there were always plenty of kids in the neighborhood. But Jay’s arrival in the summer of ’78 was right on time.

We lived in a small, two-bedroom apartment. Jay slept on our couch and made the living room his domain. As a tween on the precipice of puberty, I was utterly fascinated by this confident, lanky 17-year-old now living in our midst. It seemed like the most natural thing in the world, the way he immediately made himself at home, blasting Frampton Comes Alive on the stereo, watching Midnight Special on the tube, drinking Sprite, talking on the phone, holding court. I didn’t even try to play it cool. I thought Jay hung the moon, and he knew it.

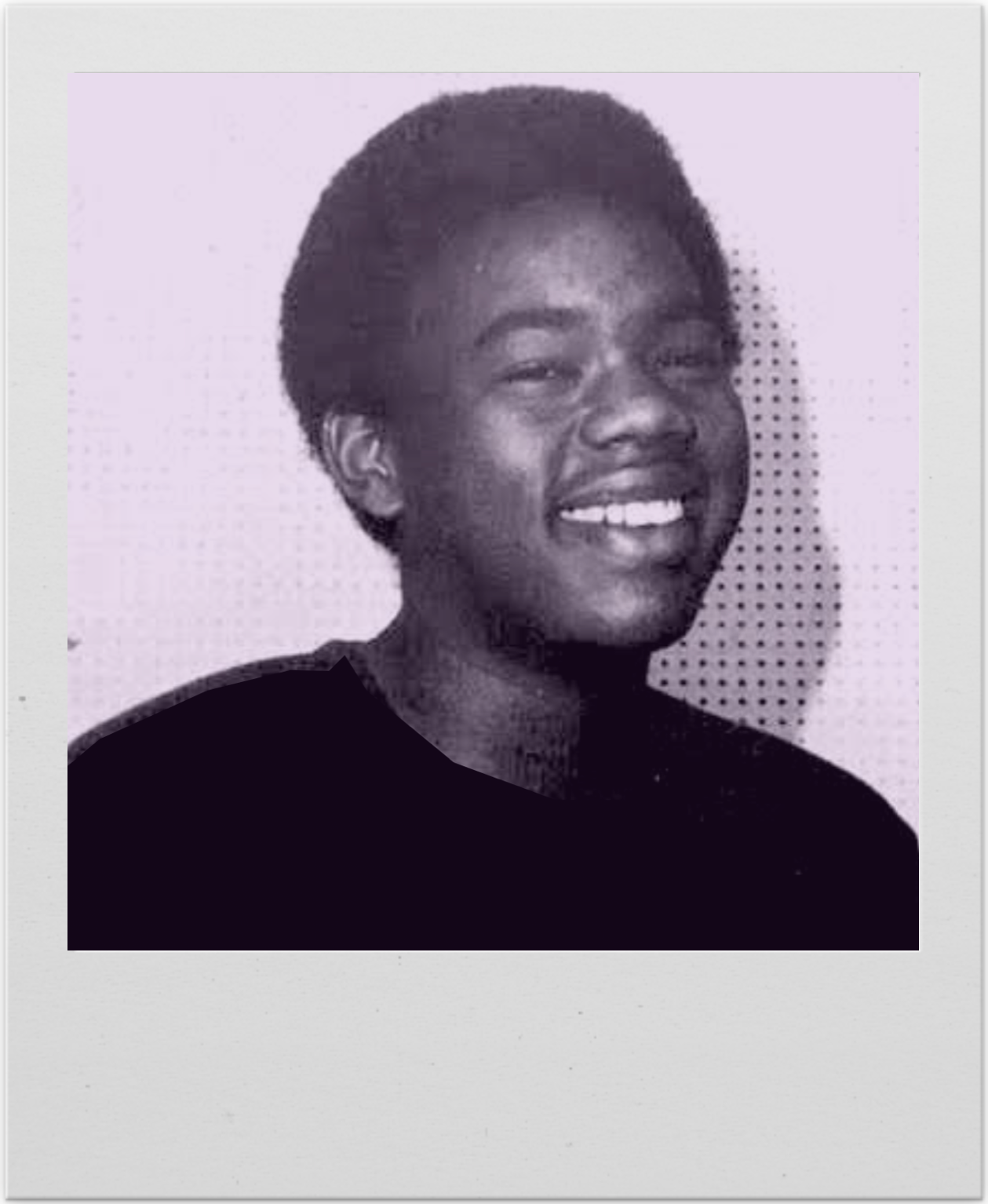

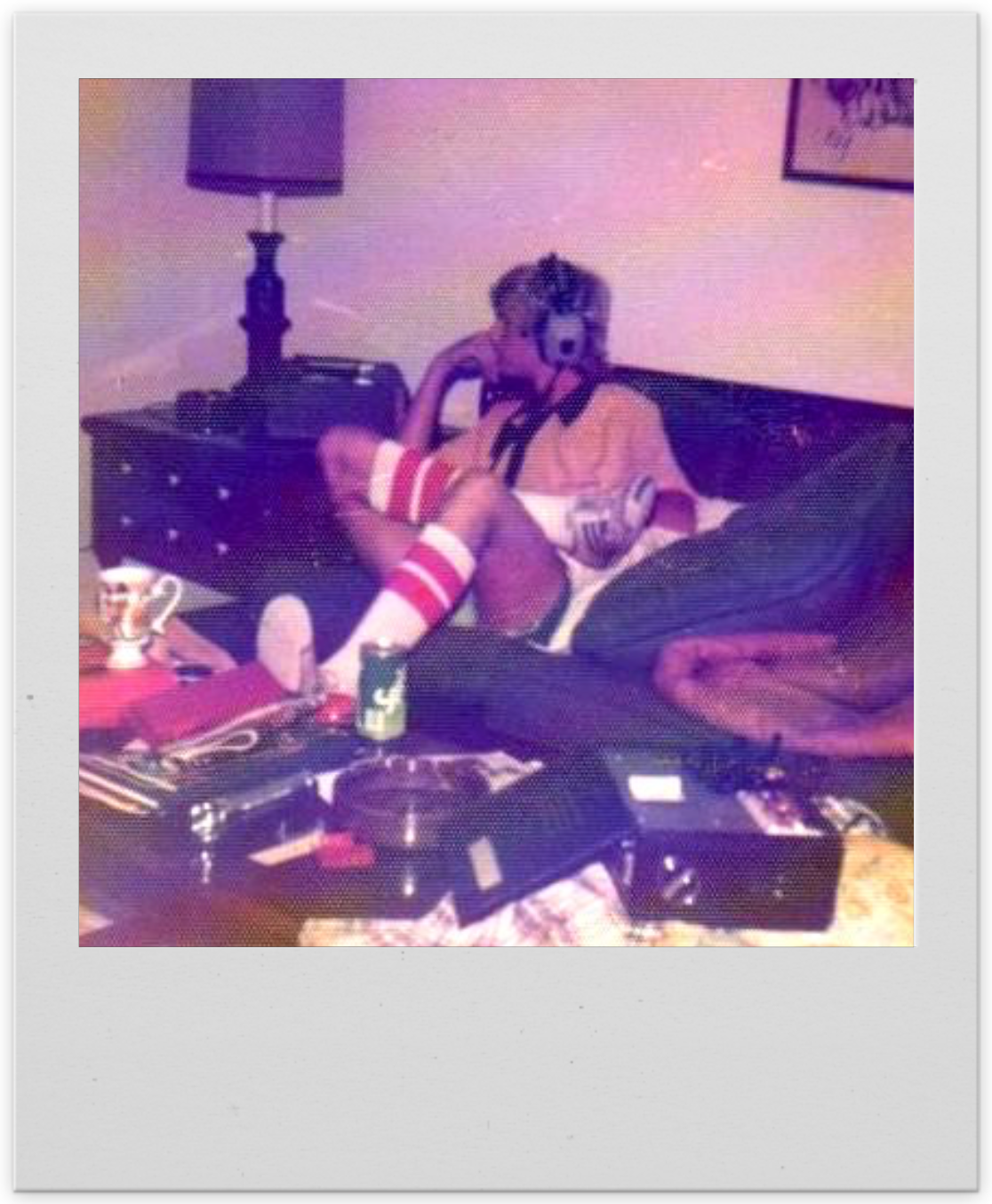

Jay Mehaffey | Summer 1978

Jay Mehaffey | Summer 1978

Warm Springs Court, Columbus GA

Dad knew it, too. Inviting Jay to move in may have sprung from a desire to help Judy, but it turned out to be the very best thing for all of us. Jay had a stabilizing influence in our home. His arrival prompted Dad to come out of his cave. Order was restored. We kept the pantry stocked, shared household chores, enjoyed regular meal times, and took road trips together.

Jay showed me how to assert my independence. Prior to Jay, I was Daddy Bill’s little sidekick, not so much a separate entity as an extension of his adult persona. I perceived Dad’s needs as my own; his moods became my moods. After Jay, I was my own man. There were three of us now, each with his own desires and responsibilities. We were a family.

But Jay was more to me than an ersatz older brother. He was like a cosmic life coach, sent by the universe to guide me through the emotional, hormonally turbulent life transition from boyhood to early adolescence. Our alliance felt all the more momentous because we knew it to be temporary. Summer’s end would mean our separation. Jay would stay in Columbus to finish high school, and I would move out west with Daddy Bill. Dad had accepted a new teaching position in Tucson, so that was where I would turn 13, begin junior high, and meet my destiny.

If Jay felt it was a drag to have a shadow that summer before his senior year, he certainly never showed it. He introduced me to his friends and let me tag along on their outings. He helped me find a job mowing lawns, taught me how to pop a wheelie on my bike, and hipped me to all kinds of music. At night I would make a pallet on the floor between the couch and coffee table, so we could continue talking into the wee hours. I’d stretch out flat, parallel to Jay on the couch above, and imagine that we were real brothers, sharing a room with bunk beds.

Our late night heart-to-hearts offered a crash course in what I should expect from life over the next few years. We talked about all the things I didn’t feel comfortable discussing with my father: cliques, crushes, flirting, fighting, parties, popularity, petty rivalry, peer pressure, the prom. I asked Jay all about the rituals of dating and how to talk to girls. He answered solemnly in great detail, stressing the importance of things like having plenty of money (chicks are expensive), when to give a girl your letterman jacket (only if you’re serious), and how to unhook a bra clasp (always use both hands). He spoke earnestly, as if he’d been tasked with a sacred mission of passing along his accumulated teen wisdom. I was riveted and hung on his every word.

Jay and I haven’t really stayed in touch since then, except to exchange Christmas cards once or twice, the way men do. But I sure hope he knows how important he was to me that summer, and how grateful I remain.

When the moving van showed up I was ready. Packing up was a breeze. After all, I’m the minimalist son of an anti-capitalist. We didn’t have that many possessions to begin with. Plus, we’d already moved several times before, so I knew the routine: put your stuff in boxes; say goodbye to all your friends.

Moving days are always bittersweet, but this one felt different. Inspired by everything I learned from Jay, I was committed to reinventing myself. I divided my belongings into two piles. One pile comprised only the essential things I’d need in my new life out west: clothes, books, trumpet, bike. We loaded them onto the truck. The other pile was all the “kid stuff” I would leave behind forever: comic books, action figures, toys.

Word got around quickly and the neighborhood kids descended like vultures. I sold everything I could and gave away the rest, pocketing a little over five hundred dollars.

“You about ready to hit the road, Bub Man?” Daddy Bill asked. “You bet,” I replied, climbing into the cab.

I didn't look back as we headed west. To the future.

12/12/12

BLUES VIEWS

"12 months in a year, 12 signs of the zodiac,

12 bagels in a dozen, 12 bars in a Blues!"

—Wynton Marsalis

"You and your woman ain't gettin' along and you're in love.

You can't sleep at nights. Your mind is on her. That's the Blues.

You can't hug that money at night. You can't kiss it."

—John Lee Hooker

"Left hand oom-pah derivatives and comping variants are rather ubiquitous in jazz piano performance practice today, so one's assimilation of said proxy and protocol remains a factor in determining the extent of one's success in efforts of contrapuntal synchrony or the efficient delineation of tension harmony,

as in the Blues."

—Eric Lewis

WHAT'S YOUR NUMBER?

WHAT I LEARNED FROM SUPERHEROES

Like many who grew up before the era of personal computers and video games, I spent countless hours in my youth reading the adventures of superheroes in comic books.

Here are 12 of my favorites and what I learned from each:

1. SUPERMAN — Rise to the occasion. Be courageous, respectful, honorable and selfless. Your strength comes more from your character than your talent. Remember that even the greatest of us has an achilles heel, and sometimes needs solitude. Usually, however, it's possible to hide in plain sight!

2. SPIDER-MAN — With great power comes great responsibility.

3. GREEN LANTERN — Your imagination and willpower are the only real limits to what you can create.

4. BATMAN — Childhood trauma can be a source of strength. Facing your fears can be transformative. And having the right equipment is half the battle.

5. X-MEN — Evolve! Celebrate diversity.

6. WONDER WOMAN — Strong women are sexy.

7. IRONMAN — Dress for success. Clothes make the man. There will be setbacks, but don't let your flaws define you. And innovate! A better version is always possible.

8. FANTASTIC FOUR — There is power in teamwork.

9. THE FLASH — Be the best at what you do.

10. THE HULK — Never judge a book by it's cover. You can't know what a man is capable of simply by looking at his appearance...especially what he might be capable of if he gets angry.

11. CAPTAIN AMERICA — Know your mission. Be willing to take a stand, even if it's unpopular.

12. THOR — Remember your birthright, but don't seek glory. If you do the job right, you'll get it anyway.

~DM

CONGRATULATIONS, MISS NELLE !

I first read Harper Lee's southern gothic story To Kill a Mockingbird when I was 12, at the Brookstone School in Columbus, Georgia.

I was too young to fully appreciate the novel's themes, but its compelling characters made a deep and lasting impression, ultimately becoming part of my personal mythology.

I've always aspired to be like ATTICUS FINCH: a beloved, respected, tireless crusader and a morally upright community leader.

Atticus is educated, honest and articulate, yet free of racial and class prejudice. He does not hold himself to be superior to his neighbors. In fact, he hides his extraordinary skills (for example, he's an expert marksman) until they're necessary. Atticus is the intersection of supreme intellectual confidence and absolute social humility.

As it turns out, I'm no Atticus Finch.

I'm more like BOO RADLEY: a pale, reclusive, misunderstood shut-in.

I keep to myself, emerging for the occasional creative, caring or heroic act. These go, for the most part, unseen, unsung and unpunished.

And I'm more like the MOCKINGBIRD: I don't do much but make music for folks to enjoy...(and that's why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird).

Congratulations, Ms. Lee, on the 50th anniversary of the publication of your masterpiece -- and thank you.

ARIZONA ~ DM on the Desert

When I was twelve, my Dad and I moved west from Georgia to Arizona. I spent my formative years there, and I still feel a strong connection to the landscape.

The desert gives you a perspective. It calms your spirit and invites contemplation, in much the same way that the ocean does in California. Play your horn into those canyons and foothills, and you'll experience for yourself the Japanese concept of ma, the sacred silence between sounds.

KNOW YOUR LIMITATIONS

"You've got to know your limitations.

I don't know what your limitations are.

I found out what mine were when I was twelve.

I found out that there weren't too many limitations,

if I did it my way."

~Johnny Cash

NUMBER 12 LOOKS JUST LIKE YOU - Part 2

NUMBER 12 LOOKS JUST LIKE YOU - Part 3

NUMBER 12 LOOKS JUST LIKE YOU - Part 1

PINBALL COUNTDOWN [POINTER SISTERS ON SESAME STREET]

EXCELLENCE SHINES ~ DM on the Grammy Awards

So true!

Here's a glimmer from 1998 which still gleams:

12 years ago today our Recording Academy awarded the Grammy for best jazz instrumental solo to trumpeters Nick Payton & Doc Cheatham, two of my favorite artists, for their tasty rendering of Hoagy Carmichael's masterpiece "Stardust."

It was one of those rare moments that occurs all too seldom in life, when excellence shines through and the universe nods in accord. Amazingly, the mind-numbing pop culture-drunk music industry briefly woke up, remembered its calling, and cast a collective vote for quality.

For a short while that year, music behaved like the meritocracy we all wish it could be.

We all voted for this record, but whenever I listen to it, I secretly believe it was created just for me.

Mine, like my big wheel or my slice of Key Lime Pie!

This entire album is a keeper, but I especially dig their treatments of "Stardust," "The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise" and "Jeepers Creepers."

Hear it and get yours on iTunes or Amazon.