Thoroughly enjoued presenting “Melodic Mastery” jazz improv workshops for Calvin University (Grand Rapids) and Kellogg College (Battle Creek). Warm thanks to professors Lisa Sung and Eric Campbell for hosting. Excelsior!

Thoroughly enjoued presenting “Melodic Mastery” jazz improv workshops for Calvin University (Grand Rapids) and Kellogg College (Battle Creek). Warm thanks to professors Lisa Sung and Eric Campbell for hosting. Excelsior!

When I first met my hero Art Farmer, he was spending half his year at home in Vienna and the other half on tour.

Occasionally concert promoters would pony up for his New York band, but most of the time Art worked with local rhythm sections. Regardless, he hired the best musicians everywhere, and his ensembles never failed to impress.

"How do your groups always sound so good?" I asked him after a knockout performance at Kimball's in San Francisco. "What's the secret?"

"Dmitri, it's simple," he said. "If you find that you're the smartest cat in the room, you're in the wrong room."

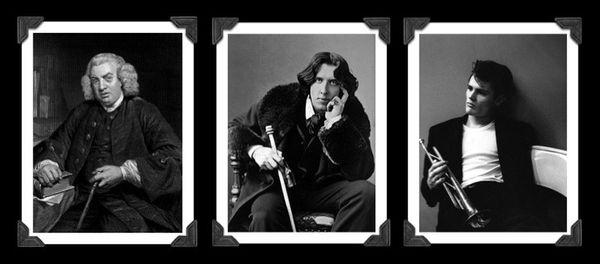

Art Farmer talked about Clifford Brown often.

The two were contemporaries, nearly the same age (born just two years apart), and had played in Lionel Hampton’s band together.

But Art spoke of Clifford Brown with a quiet reverence.

Art called Brownie "my idol” and had his initials carved into the bell of his own horn for inspiration.

“Every time I see those initials — C.B. — I’m reminded of what’s possible. I see those initials, and I work harder.”

Art would rub his thumb over the indentations, shaking his head in disbelief.

He never got over Brown's untimely death, in a car accident, at the age of 25.

“Can you imagine,” Art would ask, “if Cliff was alive today? What he would sound like now? Damn.”

The year of Scout! Train puppy to be a good home dog and road dog.

Coordinate distribution of Jazz Noir to radio and reviewers.

Prepare fresh DMG sets. Focus touring mostly in the northwest region.

Fewer gigs, higher fees, larger audiences.

Get back to playing long tones every day. Make it a habit.

Continue to eat right, exercise, lose weight and build muscle.

Take good care of Sassy, Scout, Ninji, Boo and the Fortress of Sassitude.

Plant a vegetable garden and a Japanese Maple.

Don’t be afraid. Play your way. Find your voice.

Get out from under the master’s shadow. It’s time.

This week, Sassy and I have enjoyed the hospitality of some friends who've generously provided lodging for us in their home while I play a few gigs in the area.

Their son (let's call him Freddie) is a very talented young aspiring jazz trumpeter.

Although I regularly give master classes on the road, and have done my share of classroom teaching, spending time with Freddie and his family over the past week has been a powerful reminder to me of what it means to be a serious musician and what an industry jazz education has become.

At the age of 16, Freddie has already taken advantage of more specialized training and travel opportunities than I had in my college years, and he's already twice the player I was in high school.

Freddie's days are so full that I'm actually hesitant to call him an "aspiring" musician. Not yet a high school senior, he's already playing professional gigs, studying advanced concepts and techniques, taking and teaching private lessons, listening broadly and living a decidedly music-centered life.

Freddie studies privately with two teachers: one for trumpet, another for jazz.

He's a veteran of jazz camp, Jazzschool, the Grammy band, SFJAZZ All-Stars, J@LC Essentially Ellington and Monterey NextGen.

He participates in a summer music mentoring program and leads sectional brass rehearsals for his school jazz ensemble. He's won awards in all the regional and national honors programs you've heard of and several that you haven't. And he's already performed on the most prestigious jazz stages worldwide: New York, Monterey, Montreux, North Sea, Umbria.

I never practiced like this kid, not even at Interlochen. He hits it hard for hours every day. Each morning I awaken to the sound of Freddie's horn, methodically working its way through James Stamp warm-ups, Clarke etudes, Clifford Brown turnarounds, articulation and lip flexibility exercises and chord scale after chord scale. Every afternoon he has a rehearsal or two with this or that band. Every evening he practices again.

When I was Freddie's age, my bedroom was a shrine to Lindsay Wagner and Spencer's Gifts. I had only just begun to take private lessons and didn't take them very seriously. I loved to play but hated to practice.

Freddie's room is a hardcore crucible of brass: his chair, music stand and horn are at the center, surrounded by stacks of lead sheets and method books. His walls are festooned with festival posters and images of great jazzmen. On his desk a laptop computer is open to an overstuffed iTunes library. Two speakers face the practice chair.

I spent a couple of hours trading riffs with Freddie, and am astonished by his proficiency on the horn and his familiarity with the nuances of the jazz language. He's already familiar with every classic recording I mention, and he seems to own nearly all the available Aebersold and music-minus-one collections of standards. He has a remarkably sophisticated ear for modern harmony and can toss off bebop clichés over complex changes at bright tempos. He listens to all the same jazz heroes I do, plus the latest recordings by Alex Sipiagin, Ambrose Akinmusire and Billy Buss. He already knows the tunes, licks and lore that I learned in my five years at Berklee.

The other night I invited Freddie to sit-in with me and the band on "Invitation." The audience was knocked out. He played a mature solo, including some very creative motivic development. After the set, Freddie was appropriately gracious and grateful, pausing to individually thank each member of the rhythm section. He even possesses enough charm to balance all that swagger.

After 30 years in music, I'm now at an age when I think it's important to pay it forward. It's been my belief that I have a responsibility to share what I've learned over the course of my life and career, and to mentor and encourage the next generation of musicians.

But if they're at all like Freddie, I don't have the time.

I need to practice.

"Sometimes you have to play a long time

to be able to play like yourself."

—Miles Davis

"A mentor is someone who sees something in you that you don't see in yourself...a beacon to guide you on your path. If you're ready, a mentor is someone whose hindsight can become your foresight."

—Dr. Billy Taylor

"This is not 'Nam. This is bowling.

There are rules."

—Walter Sobchak

"If I'd observed all the rules,

I'd never have got anywhere."

—Marilyn Monroe

"I'm going to show these people

what you don't want them to see.

I'm going to show them a world without you.

A world without rules and controls,

without borders or boundaries.

A world where anything is possible."

—Neo